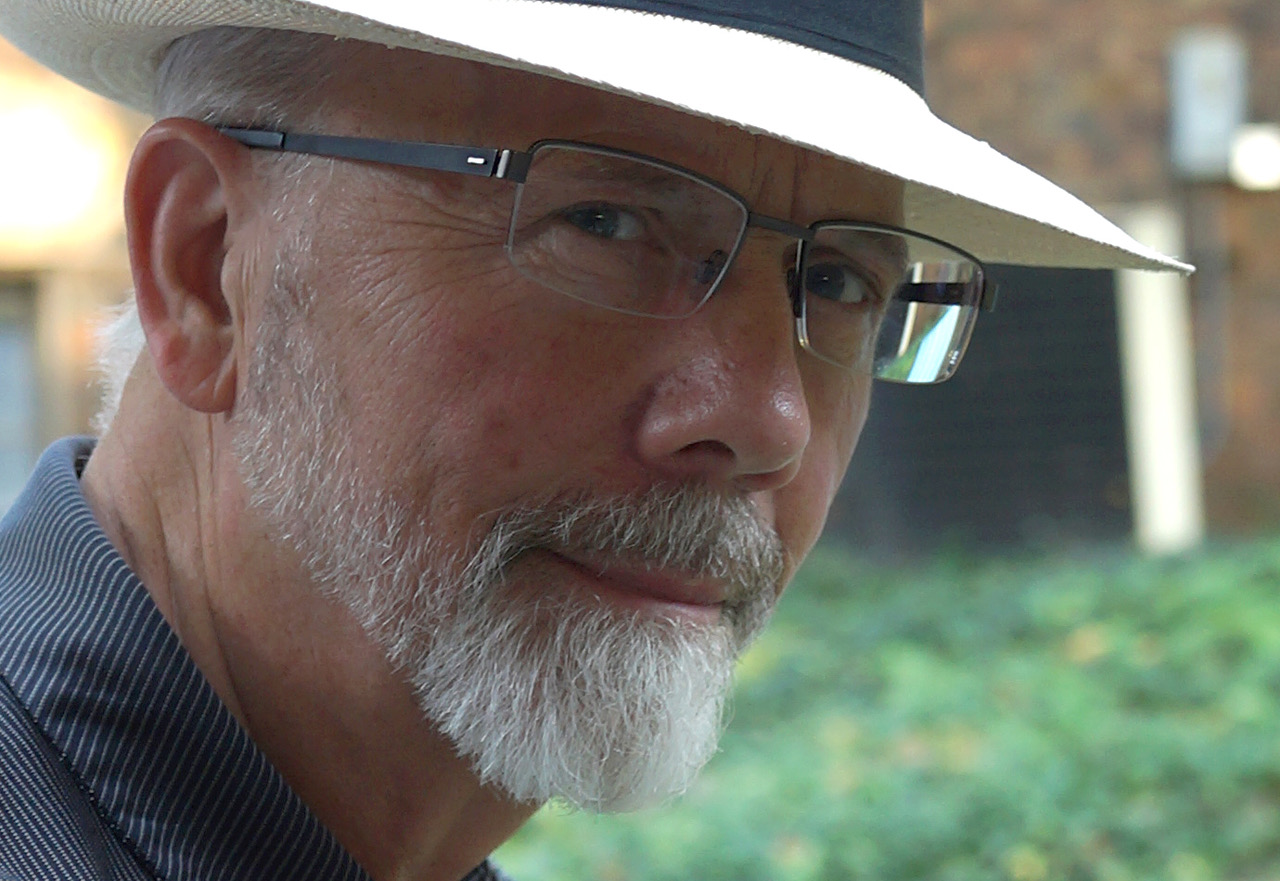

Jack Kresnak’s Career Advocacy for Children Elevates Flinn Foundation’s Mission

In his 38-year career as a journalist with the Detroit Free Press, Jack Kresnak devoted two decades to reporting on issues impacting children. His focus included “juvenile justice, child maltreatment and the mental and physical health” of children, according to his bio.

Kresnak’s efforts did not go unnoticed. Before he retired from his journalism role, he was honored by the Michigan Supreme Court for the many reforms his work inspired. It was the first time the high court honored a journalist, and the resolution was unanimous.

During even a short conversation with Kresnak, he can reveal very specific details from the work he did researching and reporting issues related to young people and juvenile justice. The stories he wrote brought about systemic change.

“Beginning in January 1988, I raised my hand to cover juvenile court and it lasted 20 years. I knew nothing when I started. Juvenile court is completely different from criminal court and I learned as I went,” Kresnak says, adding that he worked hard to gain the trust of those who are typically suspicious of reporters.

“I was telling stories that were interesting and important and changed how things worked. It was clear what was not working well,” he says.

For context, this was the late 1980s and 1990s, when the system was overloaded with issues related to “crack cocaine and superpredators,” and kids were getting caught up. As a result, youth who got in trouble were sent to facilities as far-flung as Pennsylvania, Colorado and Iowa. Visits to some of these facilities with Wayne County’s Juvenile Court Judge Patricia Campbell helped Kresnak report on where these kids were being sent.

Wayne County, responsible for more than half of the state’s juvenile delinquents, decided to create a system to provide a more efficient and cost-effective way to reform kids who commit crimes or status offenses (things like not going to school or running away from home). Using an innovative computer program, the needs of each child and their parent are quickly determined and a network of private agencies are held accountable for outcomes. “It was a unique and accurate effort to determine a child’s needs,” Kresnak said. Populations of detention centers and training schools dropped dramatically, and juvenile crime decreased.

“There were so many mental health needs out there for children and for this system to succeed, it really needed to get through to the mental health issues,” he says. “Much of it was immaturity, but also trauma and how it impacts children.”

Shining a light to bring change for children

Kresnak continued reporting and sharing stories to shine a light on the needs of Detroit area families. He draws connections between “horrific” crimes kids were committing and the practice of designating children wards of the court because of abuse and neglect. He says it’s regrettable that no matter how much he reported on the horrible abuse a kid suffered as an infant or toddler, “it didn’t matter to legislature. They just put them in prison instead of getting help,” he says.

Inspired by Kresnak’s work, Detroit Free Press publisher Neal Shine in 1993 created a Children First campaign highlighting stories to, as Shine put it, “to get in the game” to improve the lives of Michigan children. One result came the following year when the state created the Office of Children’s Ombudsman empowered to review the confidential records of cases of maltreatment of children involved with Child Protective Services, foster care and adoption. “I got tons of calls for people to look into system failures and there was no way I could look into all of them. Now, I had a place to refer people to.”

The powers of the ombudsman were strengthened through “Ariana’s Law,” as a result of Kresnak’s series on the abuse and murder of 2-year-old Ariana Swinson. Political news of the 2000 Bush vs. Gore election threatened to overshadow the local story of a little girl removed from the custody of an aunt to be returned to her parents “despite their clear lack of abilities and drinking.” Still, the story remained on the paper’s front page each day.

Many articles, fellowships and many, many awards later, Kresnak retired from the Detroit Free Press in 2008 and served as president and CEO of Michigan’s Children, a nonprofit advocacy organization, until 2012.

How Jack Kresnak joined the Flinn Foundation

During his years as a journalist, Kresnak reported on the work of the Skillman Foundation and particularly Leonard Smith, who was instrumental in establishing the foundation along with Rose Skillman in 1960 with a mission to transform K-12 education in Detroit.

Smith went on to lead the Flinn Foundation, working closely with current president and CEO Andrea Cole, who reached out to Kresnak to write about children’s mental health. Sadly, Smith died on January 21, 2024, at age 89.

Seeking his media expertise and judgment, the Flinn Foundation board members asked Kresnak to join the board as a Trustee. “They trusted my abilities and knowledge about the systems that deal with children. They thought I could bring a new voice,” he says. “I was thrilled. I love being on the board. It’s gratifying in a lot of ways and I look forward to continuing.”

As a small foundation, Kresnak says Flinn’s value is in enlisting partners to make effective change in the systems of the state and develop models that can be adopted nationally.

“Andrea is smart and engages with people in Michigan and around the country,” he says, adding that Obamacare helped lift mental health services into regular health care, “as it should be for everyone.”

Kresnak says he hopes through additional grantmaking, the Flinn Foundation can expand financial support to programs in broader geographic areas of southeast Michigan.

He also looks forward to helping Flinn pursue additional work in two areas: first, in the criminal justice system to appropriately treat those with mental health issues. “We’re working to grease the wheels to make sure not to incarcerate those who need treatment, because the issues just get worse, for children and adults,” he says.

Second, Kresnak looks forward to continued work with small agencies to support alternatives to homelessness, especially among veterans. “The whole system could use more public funding to improve access for those suffering, and there is a lot of suffering going on,” he says.

Kresnak wants everyone, particularly those who need access to mental health support, to know that the Flinn Foundation is there, fighting to make sure access exists.

“We are making sure as best as we can as a small funder to make sure the services you do get are appropriate and evidence-based and work to help people get through emotional traumas or mental illness,” he says. “We working to make systems better so that more and more people can get the help they need.”

In addition to his work with the Flinn Foundation, Jack Kresnak continues to write on a freelance basis. His first book, Hope for the City: A Catholic priest, a suburban housewife and their desperate effort to save Detroit, was published in 2015. Jack and his wife Diane have three children and five grandchildren.